Chiaretta has been a good friend of mine since my first ever kingdom scroll assignment (her AoA) where I first met her as we sat beside each other displaying our arts in competition.

|

| Kataryn Mercer, AoA |

We became quick friends. When her Maunche came around, I was thrilled and humbled to be assigned that as well. Many will remember the Kataryn Mercer Maunche of extreme painting and colors.

|

| Kataryn Mercer, Maunche |

I watched her progress in her arts to a level that was beyond what I could fathom. Her Italian was impeccable and gorgeous. And from the instant she told me that she had me in her ICP for making her scroll, I began planning. Through two computer crashes and purchases, I have saved a file that always returns to my computer holding a smorgasbord of ideas for what I would do when she was given her writ and I was assigned her scroll.

Two months ago, I was given her assignment. And then two weeks later, while I had already been plotting, she announced she was given a writ and hoped I was ready to make her scroll. I was, of course, super relieved because it meant I could ask her a few questions that I had always wanted to ask people before I made their scroll such as... what size is most comfortable for you and does it need to be a standard scroll and format for standard framing, or do you mind possibly needing to do have a custom frame created.

All of this out of the way, I opened my folder to begin.

First, she and I had discussed years ago how amazing the Lace Book of Marie de' Medici was, but my biggest frustration was that it was, technically, out of period. It is described to be from the second quarter of the 17th century. But the idea behind the papercutting, or canivet, was not something so late of a period. Canivet, the idea of lace cutting paper, is a tradition seen since 13th century in France with the nuns, thought to be considered 'cloister work'.

|

| Lace Book of Marie de' Medici, 17th century |

But I truly loved the idea of a lace cut scroll, and although there are earlier examples such as this French example from the 14th century, it didn't have the same feel as I was looking for.

|

| French Manuscript (W.93), 14th century |

So I continued searching for the perfect lacework cut from parchment as a more period source.

And that was when I realized that Chiaretta did amazing accessories, so why not accessorize her scroll? I scoured museum sites until I found the perfect extent find to make the papercut lace with. This fan is made of parchment and silk lace from the 16th century. A Venetian style flag fan. It was perfect for Chiaretta's Italian persona.

|

| Italian flag fan, 16th century, parchment-cut lace design and silk |

I loved the outer design work of the flag, and that is what I took as my inspiration for her scroll.

Now, I needed to order the perfect material. Paper, in my mind, would not cut it (haha, no pun intended). So, I spoke with my fellow scribal artists for where the best place to buy parchment/vellum would be. I knew, vaguely, the size I wanted to make the piece. So, through my searching, I found someone (a SCAdian) out in Oregon that hand crafted vellum in the medieval way and sold a variety of sizes.

Here is a link to their Etsy shop. I highly recommend their product!

Parchment in hand with a measure of 16" x 13", it was time to get started. The first thing I did was get the pencil in on what I felt would be the 'back' of the piece. There was definitely a texture difference between the front and the back, and I felt I made the right choice. There were also a few other strange things about the parchment (coming from someone who usually just works on machine made papers) such as the change in coloration, the visibility of 'this was skin' marks, and the difference in the thickness (and textures) of various areas of the parchment. Do not misunderstand me. This FASCINATED me and made me feel, for the first time ever, as if I was working in a period manner. It wasn't this perfect flat simple piece of paper. I have been doing paper cutting for awhile, so this was going to truly test my mettle.

Either way, I was excited. I have worked on parchment before and knew what I was getting into with inks, pencils, and any form of 'mark' on the surface, but this was a whole new beast.

|

| Pencil on goat skin vellum (parchment) |

In hind sight, I realized putting so much detail into the pencil was unnecessary. I will explain more about the reasoning for this later, but I was glad I got the shapes done before putting the blade to the parchment. Then, I started cutting. I used a #11 blade and my most comfortable pen grip for it. It was severely difficult at first because everything about cutting parchment was different than cutting paper. The pressure needed, the draw needed, how it felt (the tooth and bite of blade and leather), how it looked, and even how it tore if only a few fibers still held the piece in place.

|

| #11 blade and beginning cuts as viewed from the right side of the parchment |

But, it wasn't terrible! It was just a very different learning curve. Thankfully, I had done enough paper cut work to have a good idea of what I was doing. I kept tape handy, just in case, and I think that my cutting board STILL has little scraps of tape stuck to it for when I would cut the most miniscule piece and rub it into place as the heat would eventually take to the fibers of the parchment and keep what I feared was a little oops from becoming something bigger. I learned, later, that there -were- no oopses because parchment acts so much different than paper.

The actual main portion of the lace work measured 2.5" in width with the thinner, minus the triangular flag portions, measured closer to 1.5". Each inch of work along the piece took over an hour to cut, leaving an estimation of about 80-85 hours of work for the cutting, not including the prep time. 6 blades were needed (as I have no strop at home) in order to finish the whole piece.

There are a few very specific things I learned while working on cutting the parchment.

- Always always cut using a very dark mat underneath the cutting. My mat has two sides, one a light green and the other a very dark nearly black green. When I cut with the lighter, it was very difficult to tell where my cuts began or ended. When I flipped to the darker side, it was much easier to visualize what I was doing.

- There were very thick and tough areas that felt more like thin layers of horn than the paper feel of the parchment. Those areas would have been beautiful to ink on, but were -terrible- for cutting. It was easier to very carefully and slowly puncture small holes in close succession to the other and 'snap' the piece that needed to be extracted out of the way.

- There was quite a buckle in the parchment along one edge. This is NOT the fault of the person who made the piece and more just from the difference in temperatures and humidities of the two climates. I am certain, in medieval times, that the same was a problem as bundles of parchment were purchased or delivered from one local to another. Well, I found that cutting that area was an extremely difficult task due to the buckling and frustrated me like nothing I had ever known before. And yet, the next day when I returned to do more work, that area laid flat. This now causes me to agree at the sense it made that some manuscripts were known to have score lines from sharp blades for where the writing would be. Not only did it keep the writing line straight, but it helped to flatten the buckle if there was one so that writing could happen.

- There were areas which didn't feel as tight as the rest of the parchment. Almost as if the fibers were a little loose and it made the area feel spongy. There was a bite to that area that, even with a brand new blade out of the box, I could feel it drawing through the fiber as if there were burrs on the blade. Although I tried to sharpen my blade, the bite still got the better of me. I powered through, though. It just made my wrist and elbow and shoulder ache. I never knew so much of my arm muscles would go into cutting! Addendum: This is NOT the parchment makers fault either. Skin is a fussy thing and there are areas that can be more callused than other areas just as they can be more fatty areas.

- Do not wear anything on your arms! No, seriously. Everything wanted to catch. Even a watch or a ring. It is best to have clean arms, free of any hindrance and make certain your working space is LARGE LARGE LARGE! You don't want to feel the need to turn the piece and it catches on ANYTHING.

- Thankfully, parchment is nothing like paper. Paper tears very easily and parchment, I found, has a lot more give to it. Even when accidentally slicing through a small section of lacework and perhaps cutting a tiny ring, I would try the tape maneuver, but these little slices did nothing. The parchment, for any better description, worked much like leather. Any cut did not mean a malformation of what I was working on. It remained stiff and in place. That doesn't mean I didn't want to be as careful as possible, simply that the way parchment worked and the way paper worked are two completely different beasts and it is important to fully grasp and understand the material and respect its properties.

- Remember how I talked about marking all the detail work in pencil? Well, less is more when it comes to this craft. Specifically, less confusion into where there is a cut vs is that possibly a pencil line can save a LOT of grief on future endeavors.

As I mentioned earlier, I never felt like I was working in more period of a manner before. And although there were a few frustrations and difficulties, I thoroughly enjoyed the whole process! And yes, I still recommend the parchment from this maker. These spots are bound to happen, yet he did a tremendous job of keeping them towards the edge and making sure that the scribal middle area would give that amazing feel we all know and love when being worked with. I couldn't have asked for better unless I went for machine made, and that is not at all what I wanted with this project.

To keep with the theme and the time period, the words that were written for the scroll were based on lines from Aminta, a play written by Torquato Tasso in 1573, performed during a garden party in Northern Italy. Lines from the play were taken as inspiration by Olivia Baker, who wrote these words:

"Who often

makes Mars' bloody sword drop from his hand,

while

Neptune's mighty trident rattles to earth,

and even

from highest Jove the eternal lightning slips!

It is she,

our beloved and revered Chiaretta di Fiore.

She, who in

the eternal serenity

Among

celestial sapphires and beautiful crystals

Where summer

never is, nor winter,

Leads

perpetual dances

Of thread,

fabric, and finesse swirling in harmony to conceive the divine.

For mortals

dream to dance in the shadow of such beauty, such elegance, such perfection,

As does adorn our Chiaretta's celestial frame.

Earthly

words, there are naught worthy of her accomplishment.

And now here

below immortal grace

And high

fortune are seen in this beautiful image

Do I,

Margarita, Great and Fearless Queen of these Eastern Lands,

yield

further utterances and do induct this virtuoso of Florentine vestment into the

Order of the Laurel.

Done this 29th day of February, Anno Societatus

LIV, at Our Queen's and Crown's Arts & Sciences Championship in Our Barony

of Dragonship Haven."

From there, my dear friend Vince Conway graciously translated the words into Italian for me:

"Chi spesso

fa cadere da mano la spada sanguinosa di Marte,

mentre il potente tridente di Nettuno scuote

sulla terra

e persino

dall'alto Giove l'eterno fulmine scivola!

È lei, la

nostra amata e venerata Chiaretta di Fiore.

Lei, che nell'eterna

serenità

Tra zaffiri

celesti e bellissimi cristalli

Dove

l'estate non c’è mai, né l'inverno,

Dirige balli

perpetui

I mortali

sognano di ballare all'ombra di tanta bellezza, tanta eleganza, tanta

perfezione,

Così come

adorna la cornice celeste della nostra Chiaretta

Ed ora qui

sotto grazia immortale

E grande

fortuna si vede in questa bellissima immagine

Io,

Margarita, grande e impavida regina di queste terre orientali,

cedere

ulteriori espressioni e indurre questo virtuoso del paramento fiorentino

nell'Ordine dell'Alloro.

Fatto questo

ventinovesimo giorno di febbraio, Anno Societatus LIV, presso la Campionato di

Arti e Scienze de la nostra regina e corona nella nostra baronia di Dragonship

Haven."

With the words prepared, I was then able to get to the writing. I had fallen in love with a master calligrapher's album in Germany and wanted to use that for my inspiration in the cadel/calligraphy department. In the later periods, many calligraphers would create 'sample books' of styles that they were able to replicate in hopes of drumming up business for various works. This was a similar type of book and I just fell in love.

|

Werke der Schon Schreibmeister by FH Brechtel, 1573

|

I loved the gilded letters and I loved the stark black and gold of the cadel. Of course, there was also needing to delicately balance all the flourishes so that it didn't detract from the papercut lace. So I decided to focus on the gilding and less on the flourishes as I began working on the words. But first I had to design the cadel.

|

| Pencil sketch to prepare for cadel drawn on scrap paper |

Something simple with simple flourishes and making the curved spine so it would still be viewable as a letter C was important. It took a lot of work to create something that I felt fit the style of the period.

|

| Cadel of the letter "C" complete with india black ink and Winsor & Newton gold |

|

| Words done in india black ink and Winsor & Newton gold |

I was quite pleased with how both the lettering and the cadel came out. The ink used was a black India ink and the gold was Winsor & Newton brand. Both worked beautifully on the parchment. Space was left for the signature at the bottom. The cadel was made to fit in a 2" by 3" space and the letters were 1/8" high.

I wanted to keep with the feel of the Lace Book of Marie de' Medici, and one of the most fascinating things about it was how they painted over the patterned lace to make even more patterns, so I did the same with the lace work around the scroll, using the gold ink to help it take on a new quality.

|

| Winsor & Newton gold ink embellishments |

The last important part needed for a peerage scroll is the laurel wreath. And, since Chiaretta had recently changed her arms since the last time I painted them on her AoA, I wanted to add them as well. Thankfully, her arms lended very well to being done as a paper cut.

|

| Chiaretta's arms |

And, of course, adding the laurel leaves around the shield could -also- be done as a paper cut.

|

| Pencil sketch on scrap paper 2.5" x 3" of arms and laurel wreath in preparation for cutting |

After I cut it all out, gilding the shield with the gold ink fit perfectly into the feel of the rest of the scroll.

|

| Cut arms and wreath with Winsor & Newton gold ink for the shield, outline in India black ink |

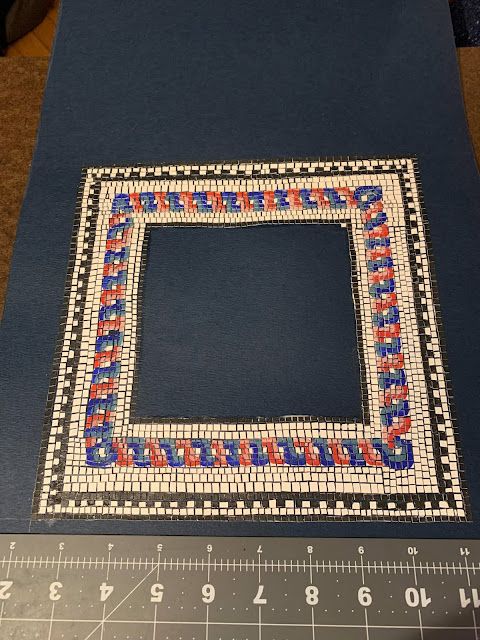

In the end, the full scroll took over 100 hours of work of cutting, calligraphy, and gilding/painting. Of course, having delicate edges, I didn't want to cause a heart attack for the heralds, so I took a board, covered it with a deep blue cotton velveteen, and carefully pinned the scroll to the fabric so it would not have to be handled but could still easily be signed by the Queen. The final result was something I was incredibly proud of and drew me closer to feeling like I worked a medieval craft than anything I have ever done before.

|

| Chiaretta di Fiore's Laurel Scroll, given on the 29th day of February and K&Q A&S competition |